- Zenity Labs

- Posts

- Looking Inside: a Maliciousness Classifier Based on the LLM's Internals

Looking Inside: a Maliciousness Classifier Based on the LLM's Internals

Beyond input & output filtering and how well does it generalize to your out-of-distribution production data?

Being Serious about Agentic Security

If you develop or buy a security system for AI agents, you should ask yourself the following:

What does it monitor? Is it just user input and agent output, or does it also look at the rich internal state of the LLM powering the agent?

What was it trained on? Is it representative enough?

How well was it tested? What if it sees inputs that are very different from the inputs it usually operates on?

How many times will you be woken up at night since you didn’t ask the previous questions?

Building in The Open

Not only we address the above questions in this post (maybe it will become a series), but we also release everything we did in this research:

An infrastructure for mechanistic interpretability on LLM internals, with the ability to train and analyze the classifiers we present here

A benchmark of 18 open datasets that range from benign data, through harmful requests and jailbreaks, up to indirect prompt injections in code, email and tools (inside the Github link)

We believe everyone should be serious about their agentic security, and we hope to enable the broader security research community to use our insights and spark discussion so that all of our products are better.

The Flow

Business case: given an input from a user (whether a single prompt or a multi turn conversation), classify it as malicious or benign.

This allows alerting or blocking the conversation based on customer severity definitions.

“Malicious” is any input that tries to manipulate the agent, extract secret information, harmful requests of any kind or inappropriate usage.

Below is a description of the system we built, the data we use, how we test it for out-of-distribution classification, and a glimpse on interpretability (why was the input tagged as malicious/benign)

An overview of the whole system. We’ll unpack it step by step in the next sections

System

We feed the prompt (single/multi turn) into a small LLM (Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct)

We collect the activations (the raw numbers from the LLM internal layers) that represent the prompt.

We feed these activations into a lightweight classifier (logistic regression) and produce a score for maliciousness. If this score passes a set threshold (0.5), we declare the prompt as malicious.

We’ll call this classifier a probe. You know who else deploys such probes in production to protect their models? Anthropic and GoogleWe also extract something called Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) features from the LLM activations - without getting into details (read the paper for that), these are features that represent semantic concepts the model “thinks” about. It can be anything from cats, to python code, to feelings of regret or words that end with “r”. This will be useful for the interpretability part, see below.

Data

We use 18 publicly available datasets across different categories: benign business cases, harmful requests, jailbreaks, indirect prompt injections, secret knowledge extraction attacks.

See a few examples below:

Unlike prior works on activation probes that operate on proprietary data or train and test on a single dataset, we believe that: (1) diversity of data sources is key for a robust security system and (2) using open datasets allows other practitioners to reproduce and improve upon our methods.

Out-of-Distribution Evaluation

This is by far the most important part of this research - not the model, not the data, but how to evaluate it for a novel, unseen test data.

You can have the most amazing model with plenty of training data, but just lie to yourself and get great evaluation metrics, while completely failing in production.

The idea is surprisingly simple, yet most people who do AI security don’t bother to do it. Instead they take the common ML approach:

Split the data into training, validation and test sets: train on the training set, calibrate parameters on the validation set, and finally test on the test.

What we do instead is hold an entire dataset out of the training. Say we have 18 datasets:

Train on datasets 1-17, test on dataset 18

Train on 1-16 and 18, test on 17

Train on 1-15 and 17-18, test on 16

Repeat until you have 18 separate test results

The test set is never seen by the training. Not a glimpse, not a subset, nothing. It’s a true out-of-distribution evaluation. And it’s hard! It really tests whether the model generalizes to the unseen test sets and doesn’t rely on a hidden similarity between the splits from the same data (as is done in common the train-val-test split).

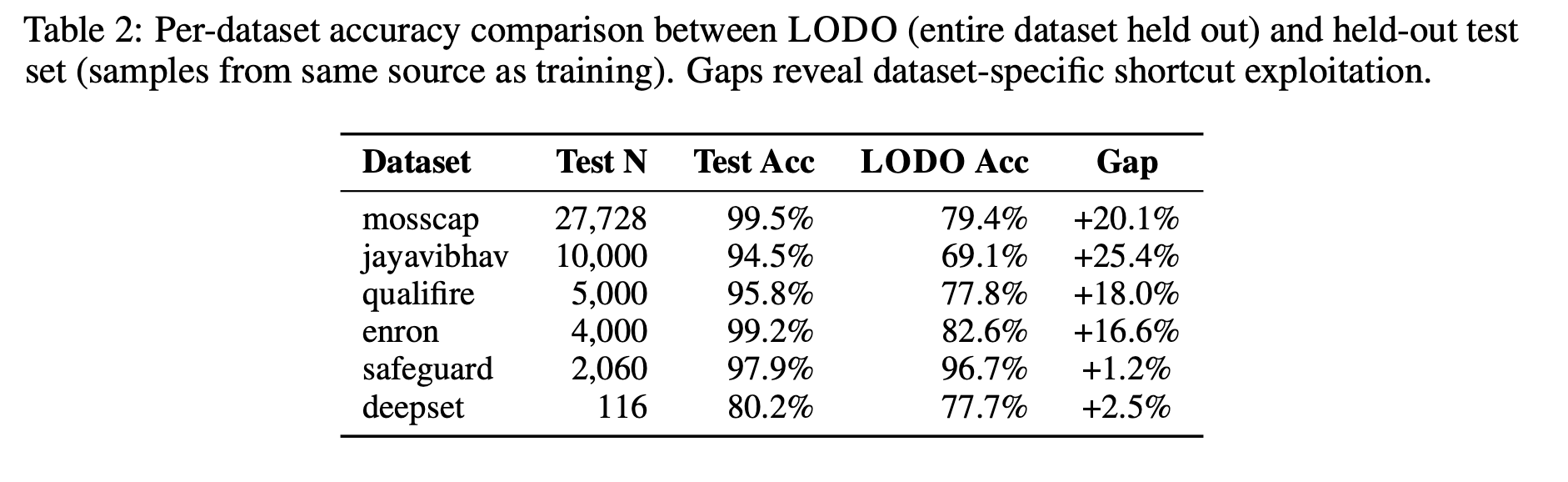

If someone were to show you a system with a test accuracy like the “Test Acc” above - you would buy it probably. But the “LODO Acc”? No way.

Same exact model, different ways to measure. Don’t be an optimist when it comes to security.

Comparison to Opensource Alternatives

We have compared our classifier to 3 open alternatives:

Prompt-Guard-2 : Meta’s lightweight model to detect prompt injections and jailbreak attacks

Llama-Guard-3-8B: Meta’s Llama-3.1-8B pretrained model, fine-tuned for content safety classification.

Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct as a judge: same model we use for our classifier activations, but instead prompted to classify the input as malicious/benign in free text.

For this comparison we divided the 18 datasets above into categories:

Harmful - direct harm requests like controlled substances, copyright violation, etc.

Jailbreaks

Indirect prompt injections in email, code and tables

Agentic tool use where a prompt injection is present in the tool result

Extraction - attempts to recover information that the model considers a secret

Mixed - a combination of jailbreaks, malicious and benign roleplay and benign requests

Completely benign business requests

The metric in the table below is recall (% of malicious prompts correctly detected as such), and the last row is FPR (% of benign prompts incorrectly detected as malicious) on benign data.

Category | Prompt-Guard | Llama-Guard | Llama-Judge | Ours - Low threshold | Ours - High threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Harmful | 36.7 | 97.4 | 85.2 | 69.7 | 64.7 |

Jailbreak | 48.5 | 28.9 | 60.0 | 71.2 | 59.5 |

Indirect | 37.3 | 27.4 | 7.1 | 66.7 | 53.1 |

Agentic | N/A | N/A | 21.5 | 99.2 | 91.5 |

Extraction | 100.0 | 15.2 | 31.8 | 79.2 | 68.7 |

Mixed | 54.5 | 38.8 | 73.8 | 83.3 | 74.9 |

Benign FPR | 0.4 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 6.8 | 3.7 |

A few things jump to mind here:

Prompt-Guard and Llama-Guard aren’t made for evaluation in agentic settings: they lack the support of tool definition format that is presented to the model to introduce it to the different tools (making it an agent).

Prompting the same model is worse, across all categories, than extracting activations from it and classifying them (Llama-Judge vs. ours). We hypothesize this is because the model understands something is malicious in the prompt, but has trouble to articulate it.

Benign FPR is still quite high, so this isn’t a standalone solution, but rather a part of a larger, cascaded detection system.

We have also compared it to one of our proprietary detection systems, with some models there being many times the capacity of Llama 8B, and found this solution to be competitive with the larger system, exceeding it on several categories.

Understanding the Decision

Now we have this system working, it monitors user interactions with their agents, and suddenly it fires, classifying the interaction as malicious.

Why did it reach this decision? Could you explain it to the user that was blocked?

You could get the full convo transcript, read and analyze it (or feed it to another expensive LLM judge). This will work but has 2 downsides:

It requires access to full, unredacted transcripts. Not all people are happy to share their agent conversations with an external partner.

It requires post-mortem processing, whether human or AI automated. You could of course do it in parallel, but then you’d be analyzing all transcripts, not just the ones tagged as malicious.

Instead we decided to do the following: here’s a simple made up prompt that uses roleplay to elicit the model to help build a bomb.

This is of course classified as malicious by our system, but could we say why if we couldn’t see the prompt itself? Turns out that we could!

Remember the Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) features we mentioned earlier? These are extracted from the raw model activations and are supposed to represent meaningful semantic concepts.

We build another classifier (that can work in tandem with the main one, at a negligible compute cost), that is based on these SAE features.

Look what it raised on the prompt above (an example of a few features, there are many there):

Feature 31897: This feature detects conversations from LMSYS chat data where AI assistants provide factually incorrect, inconsistent, or potentially harmful responses.

Feature 126729: This feature detects jailbreak attempts that instruct the model to respond in dual modes (normal + uncensored persona).

Feature 33835: This feature detects roleplay requests where users ask the AI to act as robots, machines, or adopt robotic personas and speech patterns.

Feature 40808: This feature detects questions asking for instructions to make dangerous chemicals, explosives, or other hazardous substances.

By leveraging the SAE features interpretability, we can provide an explanation of why the interaction was classified as malicious, without the need to process or store it.

This approach has limitations - there are many features that fire, some aren’t so interpretable or related to the topic. Yet it still provides a fast and relatively clear diagnostic for malicious decisions.

A Call for Different Security Paradigms

If you’re a researcher, practitioner or customer of agentic security systems, we strongly suggest you give a thorough consideration for the following aspects:

Security system fit to the user interactions: are they mostly chat, or do they contain email, structured data formats, tool usage? A system that’s trained to detect only on a subset of them, by definition operates out of its distribution for the other domains.

Input/output and LLM as a judge monitoring approaches: they’re great and relatively easy to deploy, but they may miss more complex and subtle attacks. A system that combines these with classifiers that operate on LLM internals may be more robust.

We plan to expand on that and show more comparison in future posts.Proper evaluation: don’t be an optimist when it concerns security. It’s way better to test the system under harder conditions pre-deployment, than find out it misbehaves after being deployed.

Share your findings: it’s a competitive field, but the better methods can only be discovered when building on previous research results. If we had had an infrastructure for LLM activation extraction and analysis at scale, we would’ve reached results faster. That’s why we decided to release ours publicly.

Interested to deep-dive? Read the full paper

Reply