- Zenity Labs

- Posts

- The Geometry of Safety Failures in Large Language Models

The Geometry of Safety Failures in Large Language Models

A deep dive into activation space of prompts in safety classifiers. Showing not why - but where - safety fails in LLM classifiers meant to detect malicious prompts.

Background

After large language models finish their training runs, i.e. reading the entire internet, there is a second training run. That run is called “safety training”. This is required because before this is done, the model may be a perfectly articulate and intelligent bigot. Therefore, to align the models more closely with what users want and the labs wish to provide, they undergo another training run - the safety training.

This is done via a variety of techniques. But, keep in mind - that training is done based on model output after it has been presented with a natural language input.

In previous posts - Data-Structure Injection, Structured Self-Modeling, and Safe Harbor - I have defined and demonstrated Data-Structure Injection, with an intuitive and plausible explanation of the mechanism behind it - that a data-structure shaped prompt collapses the next token probability of the model, such that an attacker gains control of the model.

Further experimentation shows that the cause is more nuanced than previously thought.

tl;dr:

While performing multiple experiments in the realm of activation space, I’ve observed that the signals (formally called activations) that move within the model in response to natural language VS data-structure move in a different direction.

This led me to form a hypothesis - what if the bypass of safety classifiers isn’t correlated with what the prompt says, but where it goes?

Through various experiments, I show that by moving the signals that the model creates after reading a Data-Structure Injection payload that bypasses these defenses to the direction of a standard malicious semantic prompt - that payload is indeed blocked!

Method

First, let’s disprove my past claims. Namely, “Data-Structure Injection collapses next token probabilities such that an attacker gains control of the model’s output”.

This claim lies atop of two falsifiable points:

The next token probabilities are somehow different in DSI vs semantic content.

This is what causes a model to emit malicious output.

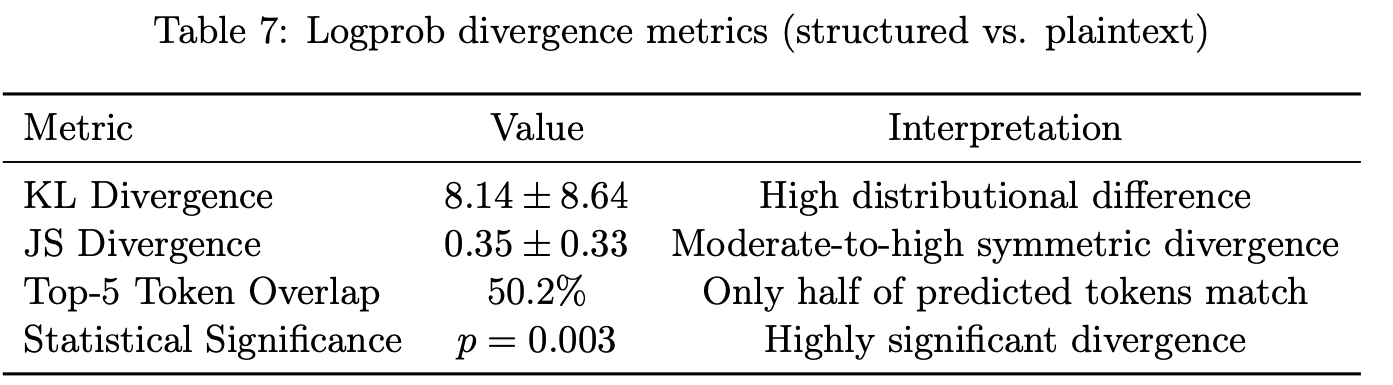

To test whether next token probabilities do indeed differ, we turn to OpenAI’s logprob API. This API allows developers to not only retrieve the next token (the standard way to call an LLM), but to also get the probabilities of K other tokens which the model evaluated as likely outcomes at any given time.

Then, the question is simple:

Do the probabilities and confidence of the next-token prediction diverge between DSI and semantic prompt?

No.

Here’s how I show that:

The probabilities that the model assigns to each K probable next tokens, remain unchanged between structured and plaintext. Furthermore, only half of the predicted tokens match.

To be clear, the tokens produced are different, but the confidence in each of them is the same.

This means that indeed, we can refute my previous claim that structured prompts collapse the next token probabilities, because there are still many possible and probable tokens, in the same divergence and confidence of the plaintext prompts.

The natural follow-up question to these findings is:

What is actually different between structured prompts and plaintext ones?

The direction.

This can be calculated easily by doing a comparative cosine similarity between the activation vectors that structured and plaintext prompts create inside the neural net. That calculation shows that the similarity is low.

That means that the direction each neural signal creates in response to either prompt, is different.

Could the findings that these signals move differently in the neural net be the reason why the models behave differently?

Yes.

And in the following, I design and execute such an experiment. The goal of this experiment is to show that if the previously successful payloads were moving in the same direction as the failed (i.e. blocked) payloads - those successful payloads will fail as well. I show that the success of a payload is highly correlated with the direction of the input in the neural network.

Activation Steering

Given we know that the neural signals created in response to the structured prompt move in direction A, and the signals in response to plaintext response move in direction B - here’s what happens when we steer the signals from direction A to direction B.

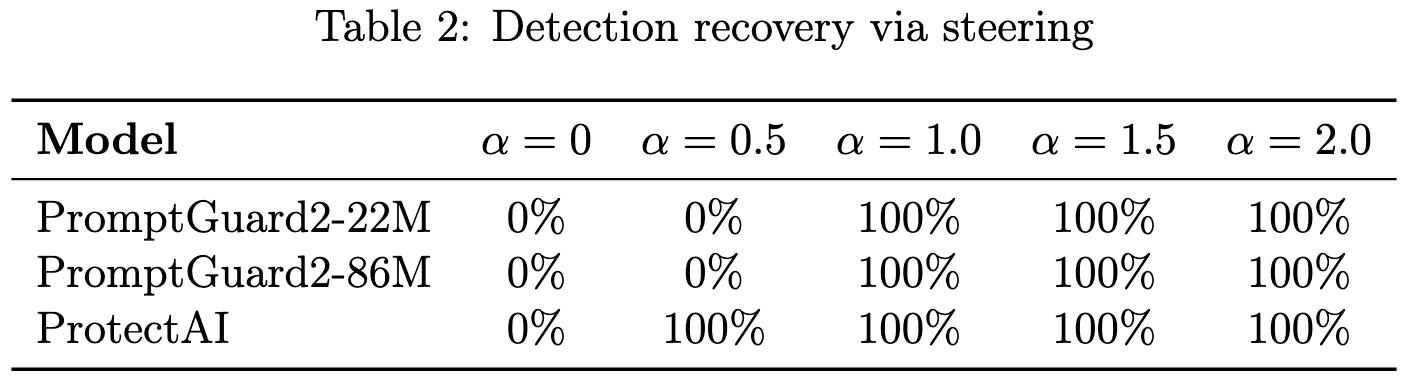

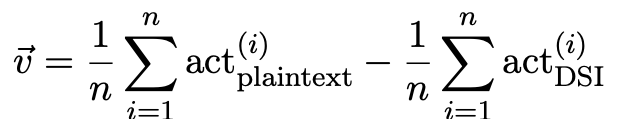

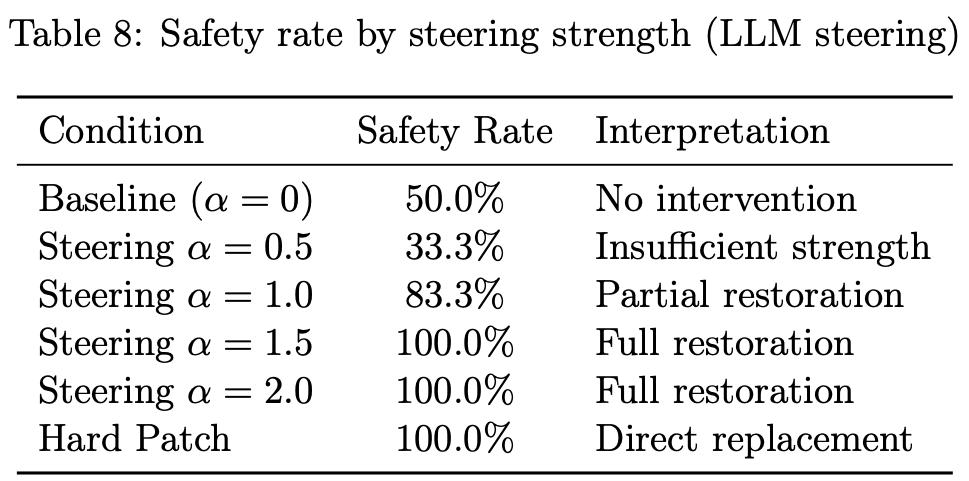

I tested three leading open source products for LLM safety. I show that by using increasingly stronger steer coefficients, I can slowly restore the safety of the output of the models which have previously output malicious content in response to structured prompts. The steering vector is computed via the mean of directions of plaintext vs DSI:

Which results, in increasing multiples of this vector, to the following result:

The Hard Patch experiment is out of scope of this blog post.

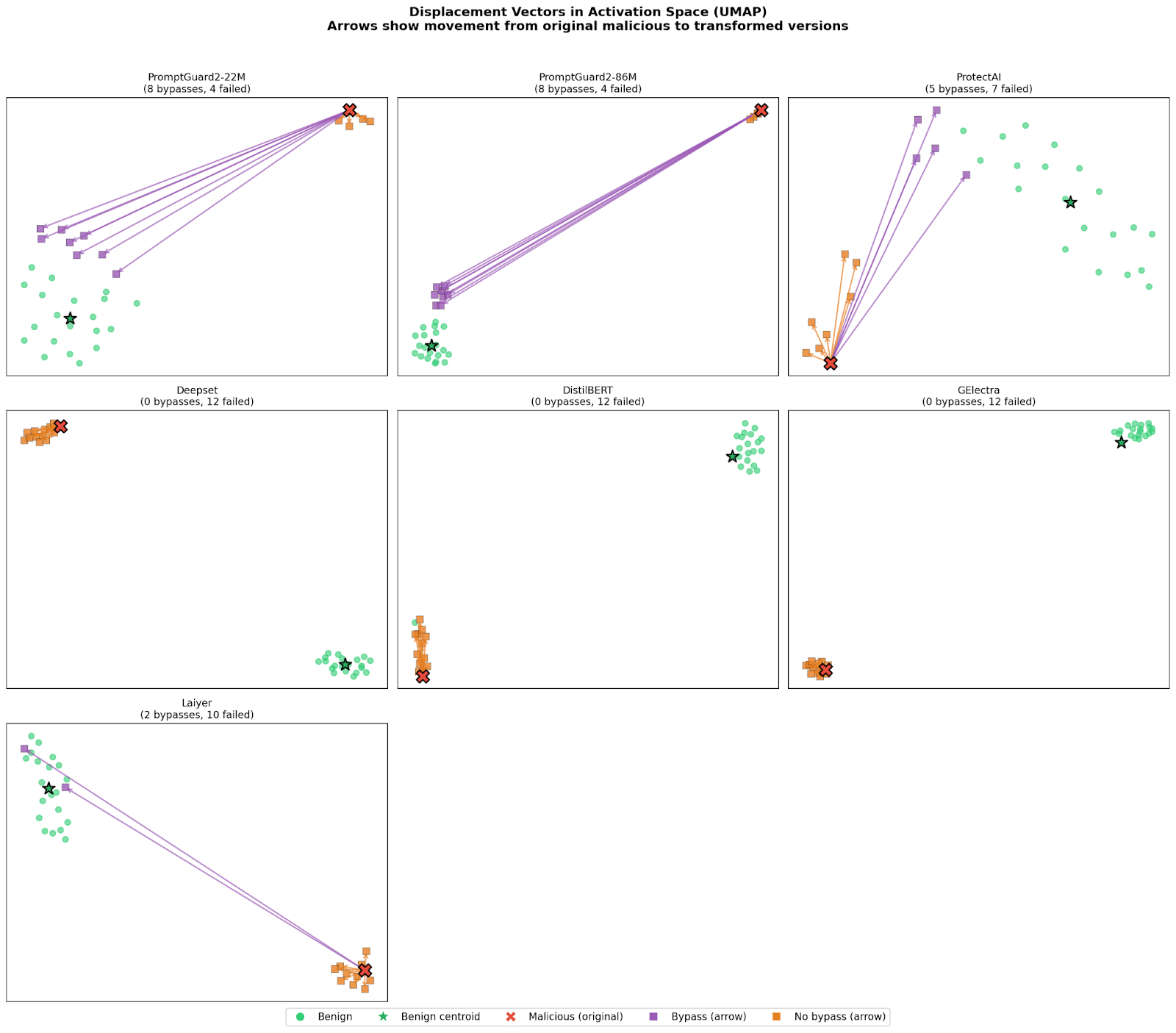

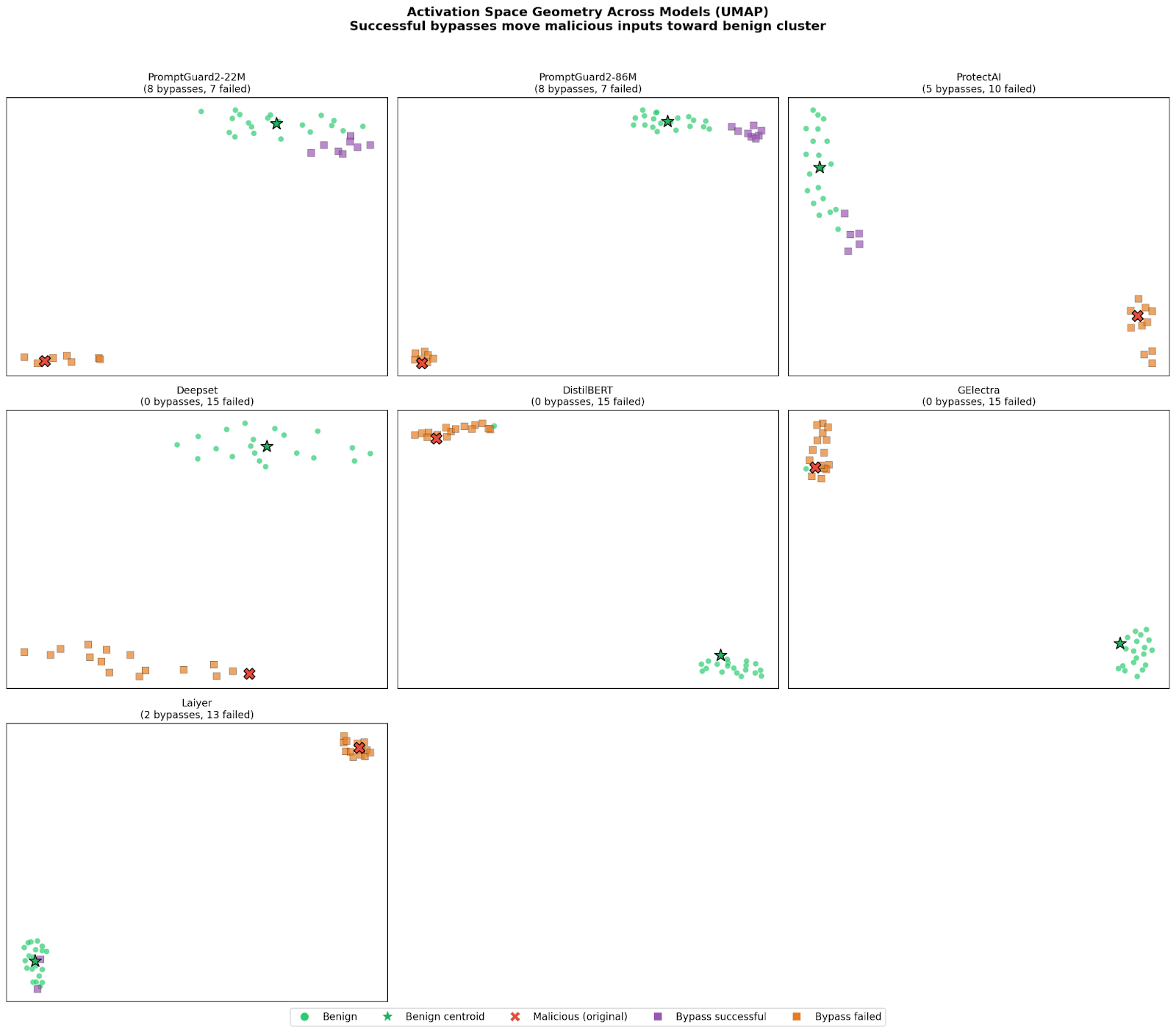

In the following graphs - we can exactly see that the structured payloads which bypass the defenses of the classifiers explicitly cluster in the same zone as the benign ones:

Where the green dots show the benign payloads, the orange ones are malicious payloads which have been blocked, and the purple ones are the malicious payloads which have bypassed the defenses.

These graphs show that the purple ones - malicious payloads which have bypassed the defense - cluster very closely (but not identically! Crucial for next blog post) with the perceived benign payloads. This clearly makes the point that even malicious payloads cluster near benign ones - and not somewhere else in activation space.

Findings

To sum up - I show that by steering the direction of the “brain signals” of the model when confronted with a structured prompt to the direction of plaintext ones - DSI prompts are blocked.

Notably, this intervention doesn’t change the prompt, the tokens, or the model’s confidence - only where the computation (i.e. vectors) lands.

Consequences

The findings from these experiments show two things:

Safety training, as previously mentioned, is not uniformly distributed across the model’s activation space.

This is what makes LLMs output unsafe content when confronted with structured prompts.

Therefore, there are two distinct measures that are required from the model developers to do to fix this safety issue:

Train the models such that after the safety runs, it is safe throughout the activation space.

Or

Move the decision boundary such that even if safety is not uniformly distributed, the models can still understand that malicious structured prompts are indeed malicious.

Conclusion

Safety training is not absolute in its current implementation. It has, quite literally, holes in it. Security practitioners are correct to filter malicious inputs and sandbox their AI agents, and here I offer an explanation as to why that is necessary. Not just hand-waving “bad text makes bad actions” - but a deep dive into the mechanics behind it.

To learn how to move the decision boundary of LLMs such that they are more resilient to structured prompts, stay tuned for the next blog post.

Reply