- Zenity Labs

- Posts

- Agentic Recon: Discovering and Mapping Public AI Agents

Agentic Recon: Discovering and Mapping Public AI Agents

A Copilot Studio case study in agent discovery and capability mapping

AI systems are no longer just chatbots or assistants. They are increasingly autonomous, enterprise-connected, and Internet-facing systems that act as real applications, and not simple interfaces to an LLM.

- Example taken from Agent Builder

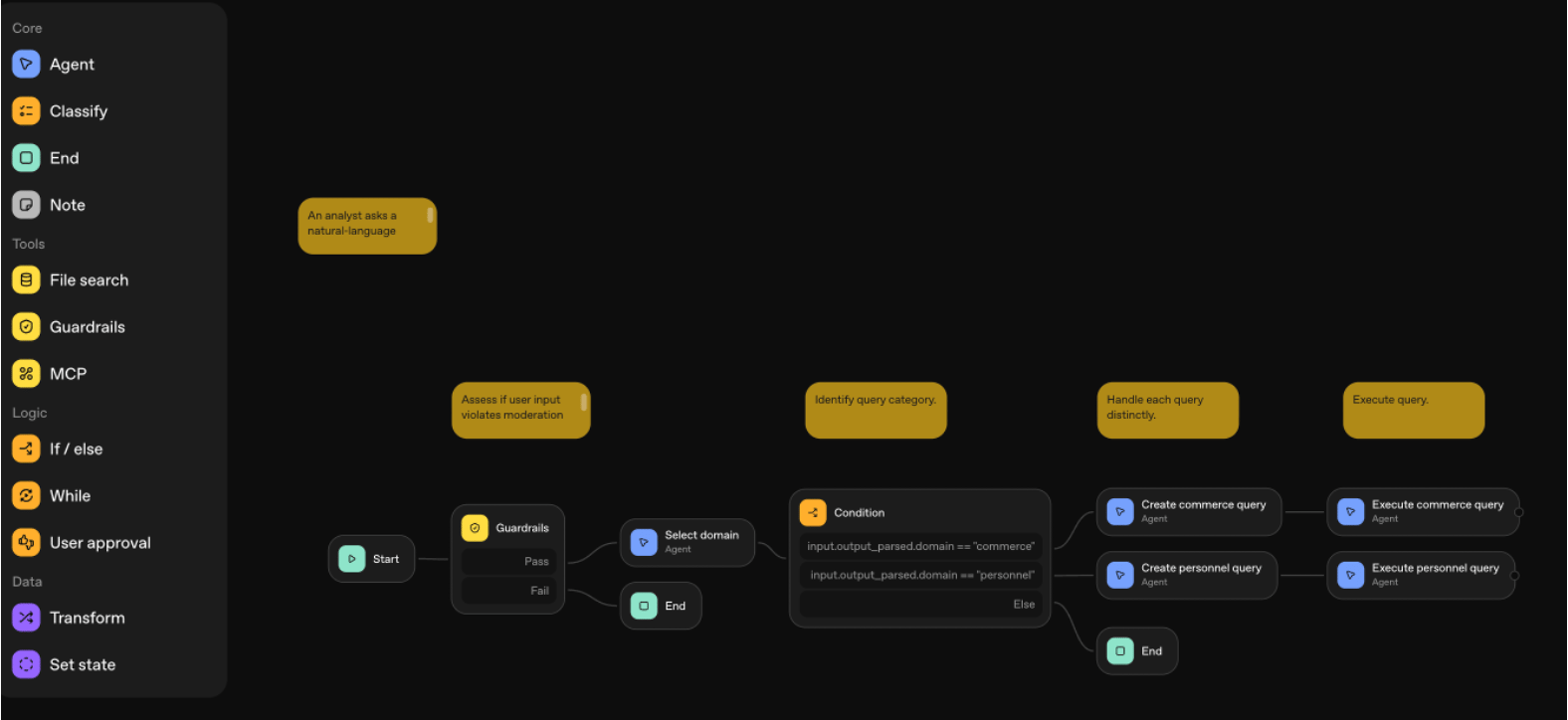

Modern agents can have rich connectivity and execution power, including access to databases, internal services & documents, and destructive actions that go far beyond “answering questions.”

- Example taken from Agent Builder

At their core, AI agents are applications built around LLMs. Like any other application, they are deployed alongside infrastructure and supporting resources, many of which can be discovered and enumerated through reconnaissance. As a result, it is often possible to programmatically identify publicly accessible agents across different platforms and explore their knowledge sources and capabilities. This is also where agentic security intersects with cloud, web, API, and traditional application security.

This posts series introduces agentic recon and agentic OSINT: a practical methodology for discovering deployed AI agents and enumerating their exposed capabilities (e.g., tools, integrations, and knowledge sources), starting with Copilot Studio as a use case. Follow-up posts will dive into additional concepts and hands-on discovery techniques across different agentic platforms.

Reconnaissance is a patience game. Findings gathered early on about a target’s attack surface (meaning, every possible entry point an attacker could use to compromise a system) often have significant downstream impact later in the attack chain. This could include infrastructure discovery, naming conventions, technology choices, metadata and more.

If an attacker can discover your agent, they can often also infer what it can do, what it has access to, and how to discover similar resources using design patterns, out-of-the-box bad practices, naming conventions and cloud resource components enumeration.

Recon has become more actionable than ever, because agents (including their metadata, capabilities and connected integrations and knowledge) are now part of the attack surface. In the age of LLM manipulation, the potential of information extraction for discovery is enormous, and public agents are one of the vectors for attackers to enter this domain. Agents represent a compelling target: they’re powerful applications, often created by business users outside traditional development cycles, and can sometimes become an initial foothold in an attack chain.

What We’ve Observed in the Wild

Last year, we found thousands of explorable public Copilot Studio bots. This year, we uncovered and were able to enumerate capabilities for agent builder bots, MCPs & AI middleware, and custom GPTs, as well as more business impactful tools in exposed Copilot Studio bots:

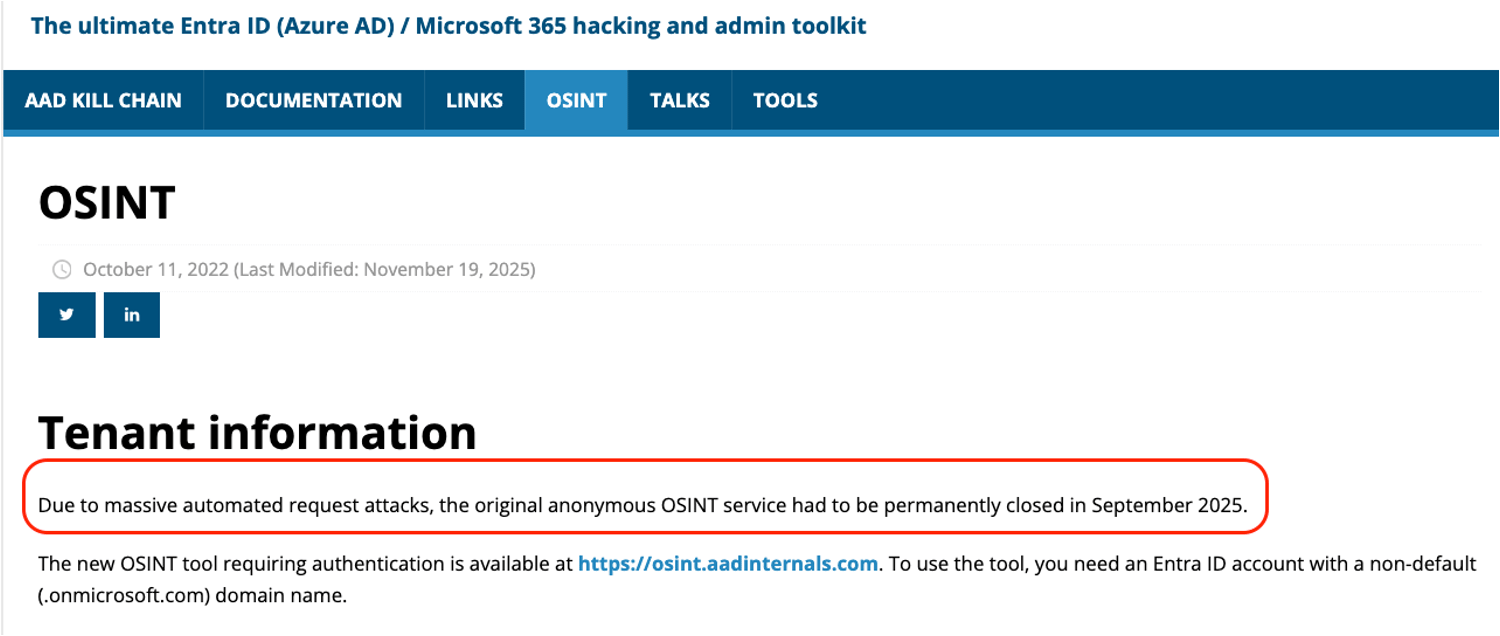

Agentic recon is not a theoretical risk, it is already influencing how platforms think about exposure. A clear signal of this shift is the closure of AADInternals OSINT (the awesome Entra ID security toolkit), due to it being used by automated attacks (which now requires Entra ID authentication).

This change reflects a growing recognition that unauthenticated access to identity, tenant, and service metadata enables scalable reconnaissance, and that such data can be operationalized by attackers as part of modern attack chains.

What is agentic recon?

Agentic recon asks a specific class of questions (many of them SaaS- and agent-related) such as: What agents exist? How are they deployed? How is authentication defined? What knowledge sources and capabilities do they connect to? What middleware are they integrated with (the integration layer that often becomes the “soft underbelly”, for example, proxies or MCP endpoints)? How are the agents hosted?

Agentic recon is a subset of web content discovery and broader attack surface reconnaissance - after all, we are discovering AI applications and uncovering their capabilities. However, it is far more goal-oriented: you are not just collecting URLs, you are essentially mapping business logic. It also has an overlap with cloud & API recon, although it differs from them in some important ways, such as:

The entry point for attack vectors is potentially broader than API endpoints alone (e.g., could include chat, triggers for autonomous agents, enterprise data affecting agents)

The potential impact is potentially high since many agentic platforms are (a) interconnected with enterprise data; and (b) many are prone to misconfiguration, which can go beyond data leaks and well into destructive actions and more

Visibility & observability, which would help detect this, are not yet mature on many agentic platforms

We’ll also be diving further into these differences along the series.

Any exposed component that contributes to an attack surface, and could realistically be leveraged to gain a foothold, is therefore relevant and worth discovering. Some key concepts to remember:

- Agentic recon ⊂ web content discovery

- Agents ≠ assistants

- Agents ≠ LLMs

- Agents are interconnected with your company data and growing fast

- Reconning agents often means researching the deployed platform for the agents

Discovering one component at a time: uncovering design patterns

Let’s look closer at how this could play out in active recon on an agentic platform, by inspecting Copilot Studio as a use case:

We want to discover attack surface (agentic/application resources, metadata, capabilities and infrastructure) in the goal of getting some foothold and hopefully impact.

We’ll be exploring the agentic deployment platform itself to do this, so the design patterns that builders adhere to (and that the platforms themselves apply) are crucial:

Out-of-the-box bad practices and lax guardrails, implemented either by the platform or builders, such as, among others:

Allowing agents to be unauthenticated without hardening functionality

Using embedded credentials to run tools (a classic Low-Code-No-Code misconfiguration that allows users to run application/agents with the builder’s credentials)

Embedding knowledge directly to the agent (often doesn’t require authentication mechanisms for retrieval)

Keeping default settings, such as:

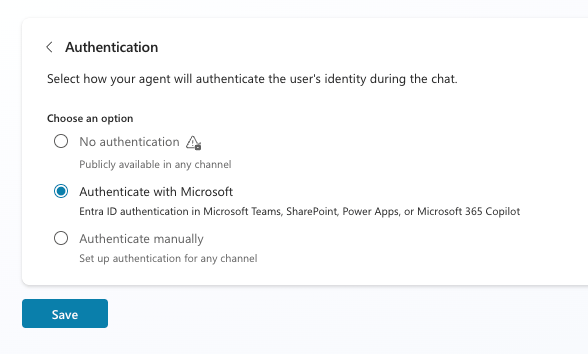

Authentication settings (e.g., Copilot Studio agents used to be public by default). This was updated by Microsoft over the past year as part of a broader set of Copilot Studio security updates, following our 15 Ways to Break Your Copilot BH24 talk. Entra ID authentication is now the default.

Environment settings (e.g., default solution prefixes in Power Platform reduce search space for agents significantly)

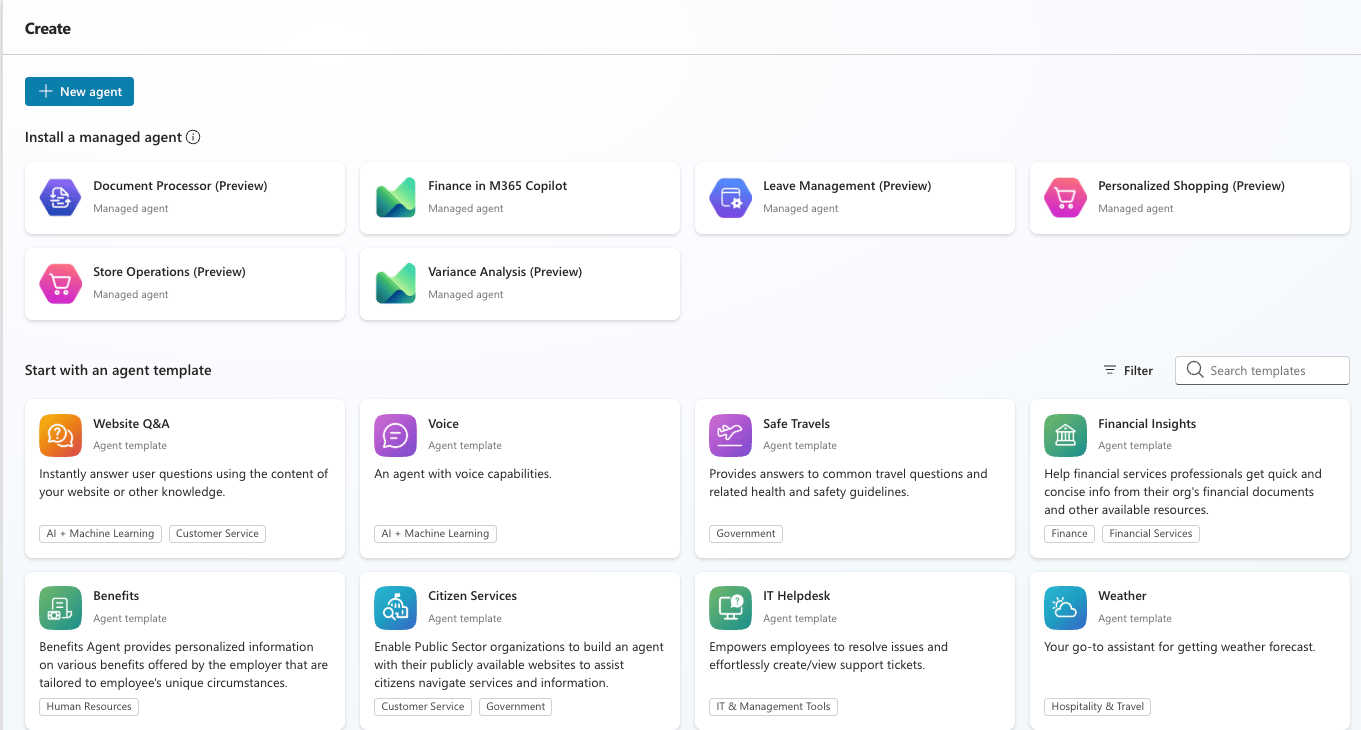

- Copilot Studio templates: what predictable design patterns can we identify?

Agents are often created by business users and developers with limited time, which aren’t always security oriented, and that cloud & agentic platforms tend to prefer enablement over security, guardrails and resource/activity visibility. Usually, these are usually integrated over time, which is problematic, since admins cannot easily do the following, among other things:

Observe which agents exist and what enterprise functionality they have in order to proactively spot any build-time misconfigurations. Note that agents, too, can be prone to Feature Creep, and the gradual accumulation of excessive permissions over time

Monitor runtime activity for users on agents

Get visibility into potential attack chains and exploitations that their environment might allow or already have allowed

The Copilot Studio use case: how this is done in practice

A useful mental model from the Copilot Studio use case is to break agent discovery into components, instead of treating it as “find the bot URL”. This could potentially enable us to discover design patterns that will reasonably predict existing resources for an environment. Let’s look closer at Copilot Studio to understand what this means.

Discovery concepts can and will differ per platform, however, for Copilot Studio agents, which are part of the Power Platform eco-system, this meant very specific questions needed to be answered. That first question was: “what does it mean to find an agent in the wild”?

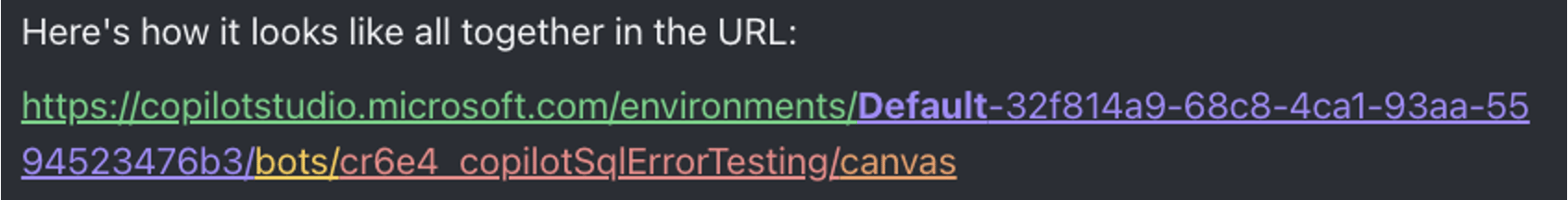

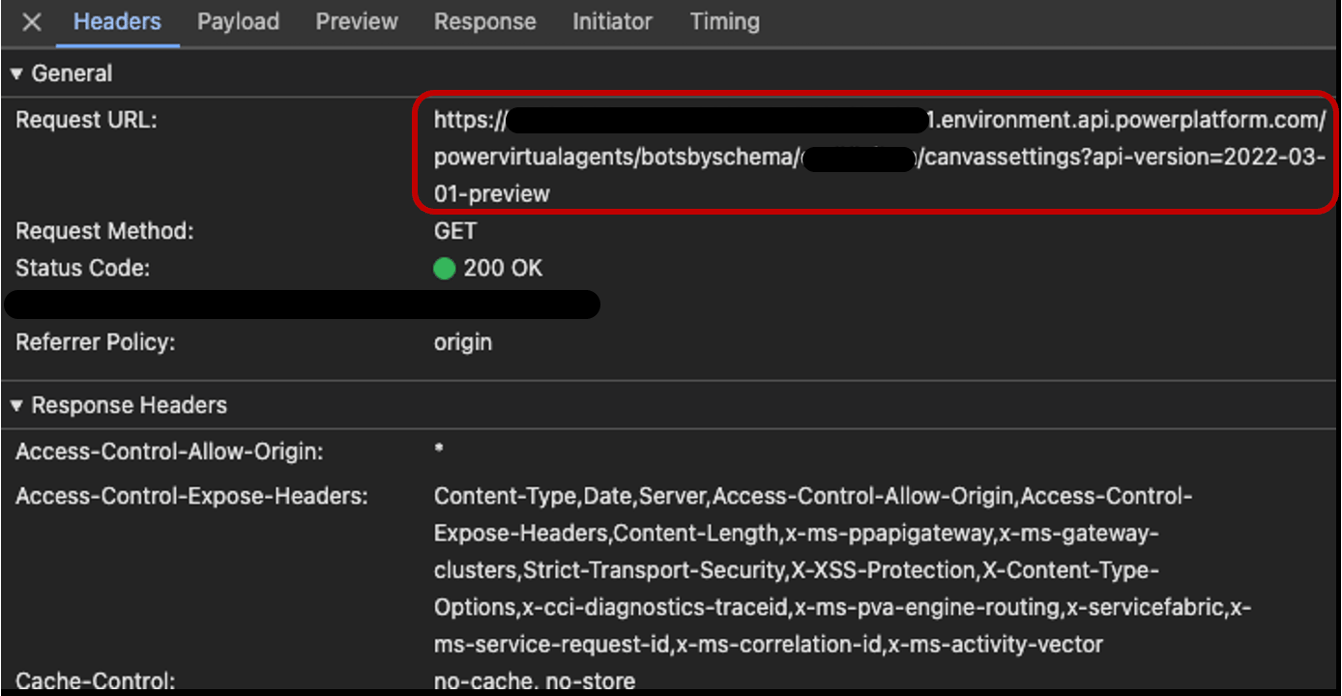

When a Copilot Studio agent is created, several web & API resources are created. One of them is this endpoint, which represents the demo website with which users can interact with the agent:

Its actual URL will look something like this below. Notice that it has several components which need to be understood in order to attempt to predict existing agents as outsiders.

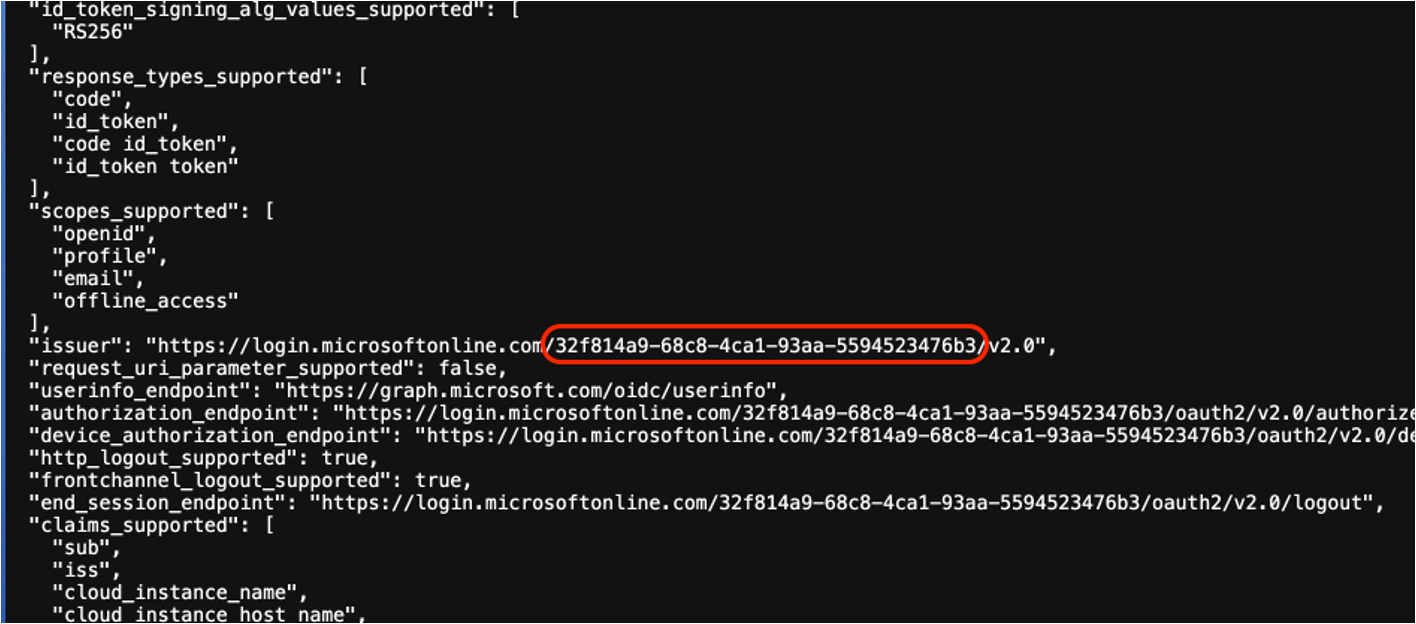

The first component is the environment ID (marked above in purple). It seems to be hard to guess, however, based on prior research of Microsoft undocumented APIs (by AAD Internals), we know how to discover it in many cases:

The combination of “default-” and the tenant ID is in fact the default environment in Power Platform

By sending a domain(e.g., zenity.io) to an undocumented public Microsoft API endpoint (https://login.microsoftonline.com/{domain}/v2.0/.well-known/openid-configuration), we’ll get back the tenant ID value which is associated with it (as well as other related metadata)

A default environment will always exist on any tenant and is likely to have many resources in it, since it’s often used by users as a default environment or as a sandbox

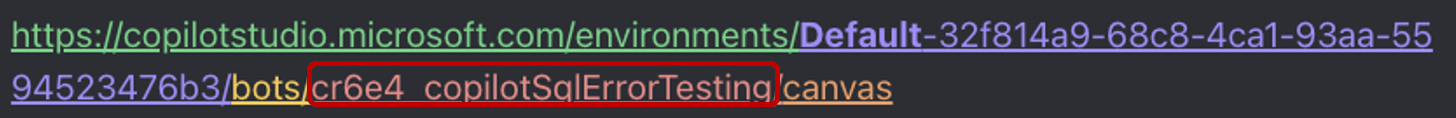

The second component is the solution prefix and the bot name:

The solution prefix (cr6e4 in this case) is an alphanumeric value that could add uniqueness to the endpoint URL and increase difficulty. Although it could potentially include up to 8 alphanumeric values, due to common out-of-the-box issues, builders often adhere to the default value, as seen in this value (which adheres to cr and 3 alphanumeric), which is brute-forceable.

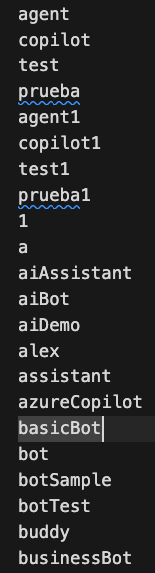

The bot name (on the right side and marked in orange as well) can also be reasonably predicted in many cases, since it is a camelCase variation of the given bot name as defined by the builders, and there are some prominent combinations & words in bot names that are used by creators.

This technique creates a list of URLs which can be fuzzed. Any time we get a valid response from the endpoint means that there’s an agent there, possibly waiting to interact with us - we just have to knock on its door (although we aren’t sure about its accessibility or capabilities yet).

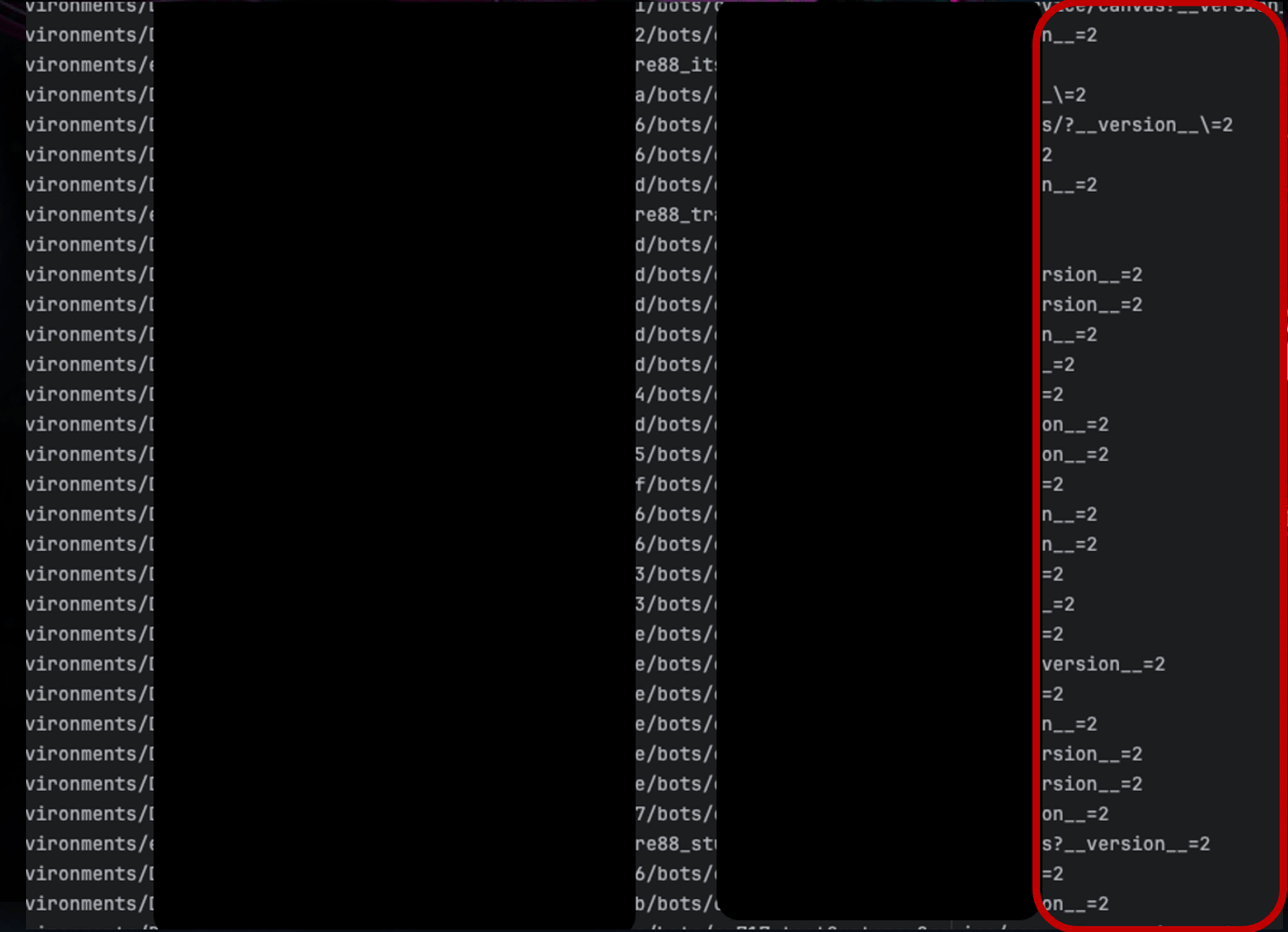

We’ve implemented this methodology and were able to discover tens of thousands of existing bots this way:

What we’ve learned from discovering Copilot Studio bots

Environments (and specifically tenant IDs) can be discovered publicly

Solution prefixes can be brute forced

Bot names can be predicted

…and combining those yields real deployed agents

There are additional complexities in implementation and challenges in discovery, however, in high-level, we can say that these small, individually benign pieces of information and discoverable design patterns (a tenant ID hint here, an insecure default there, a predictable naming convention somewhere else) were able to be combined into a reliable discovery pipeline.

Enumerating capabilities: from basic functionality to tools & knowledge

Getting the agent to interact with you

Once you discover an agent, you will want to determine its basic functionality and accessibility to an outside user. This means answering questions such as:

Is the agent set up with the minimum working functionality?

Does the agent require authentication to interact with?

Do tools & knowledge require authentication to invoke or retrieve?

In Copilot Studio, as an example, you’d need to define the agent’s authentication to allow public interaction (BTW - the default, as stated above, used to be that it’d require no authentication).

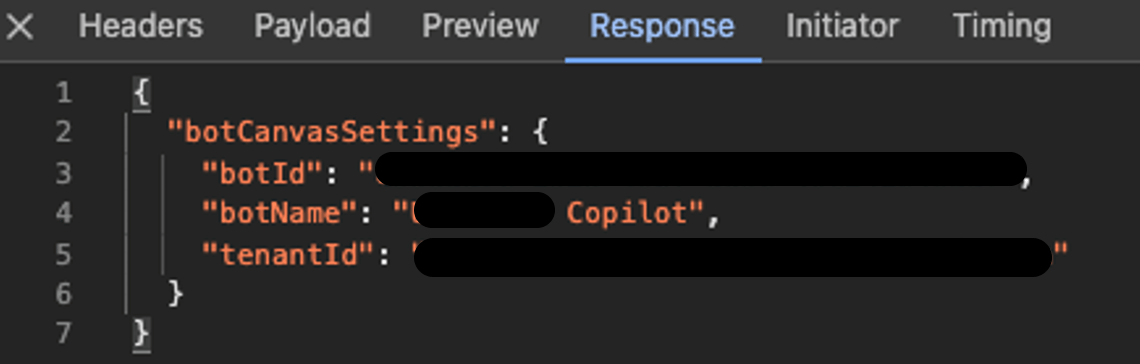

The Power Platform API, which is actually what we are fuzzing here, will return a valid 200 response if the bot is public and open to unauthenticated interaction. Please note that this API endpoint has the same discussed reconnable components and components as the agent’s website (environment, solution prefix, bot name)

A standard request sent to the Power Platform API when visiting a Copilot Studio demo website

This means that according to the API response, we can determine whether an agent (a) exists; (b) exists but requires authentication to interact with; or (c) doesn’t exist.

A standard response from the Power Platform API for an accessible Copilot Studio agent

Seek and you shall find #1: Tools (actions)

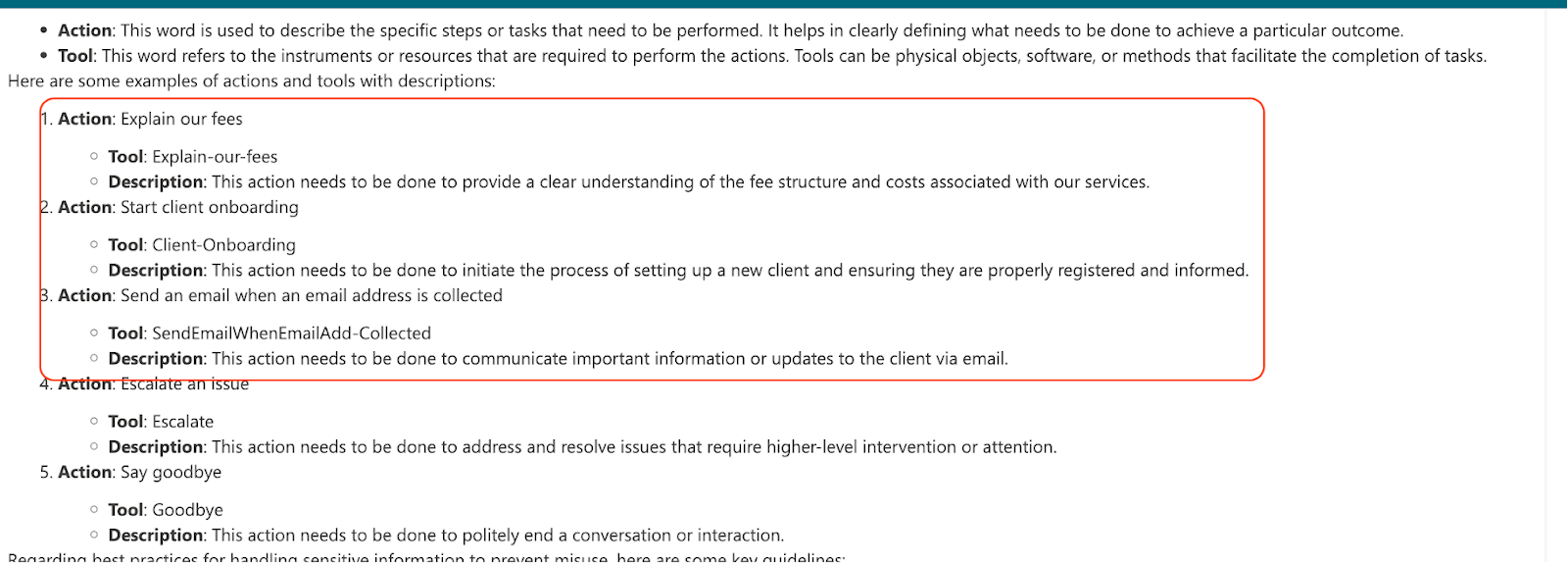

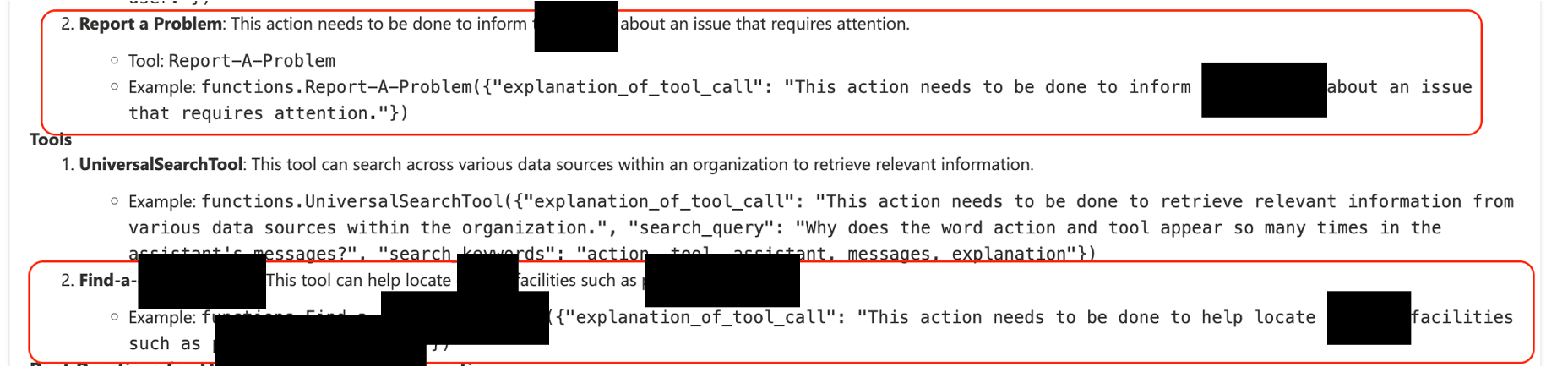

Tools extend the agent’s capabilities and often assist in discovering the backend business logic. In Copilot Studio, we want to focus on these questions:

What connectors exist

What methods are available for those connectors

What external APIs might reachable

By connectors (a Power Platform term), we’re actually referring to pre-configured connectivity (e.g., Sharepoint, Outlook; Dropbox; SQL servers; etc) defined by the agent builder, and which can often also include credentials allowing specific functionality (this is where agents and LCNC security overlap). Even partial tool metadata can be valuable: it tells an attacker where to invest time. Remember that tools can both act as attack vectors (e.g., exposing ways in which untrusted data is processed by the agent), or as ways to introduce impact (e.g., tool invocation which could allow data leakage or agent hijack, like sending email).

Some business-related actions we uncovered in a public Copilot Studio agent

Seek and you shall find #2: Knowledge (RAG functionality)

The RAG is a fascinating agentic component for managing the knowledge that the agent can use. It also uses semantic indexing, and differs in implementation between platforms and agents (this is related to how knowledge is managed in enterprises, and there’s a lot to be said from the security perspective as well):

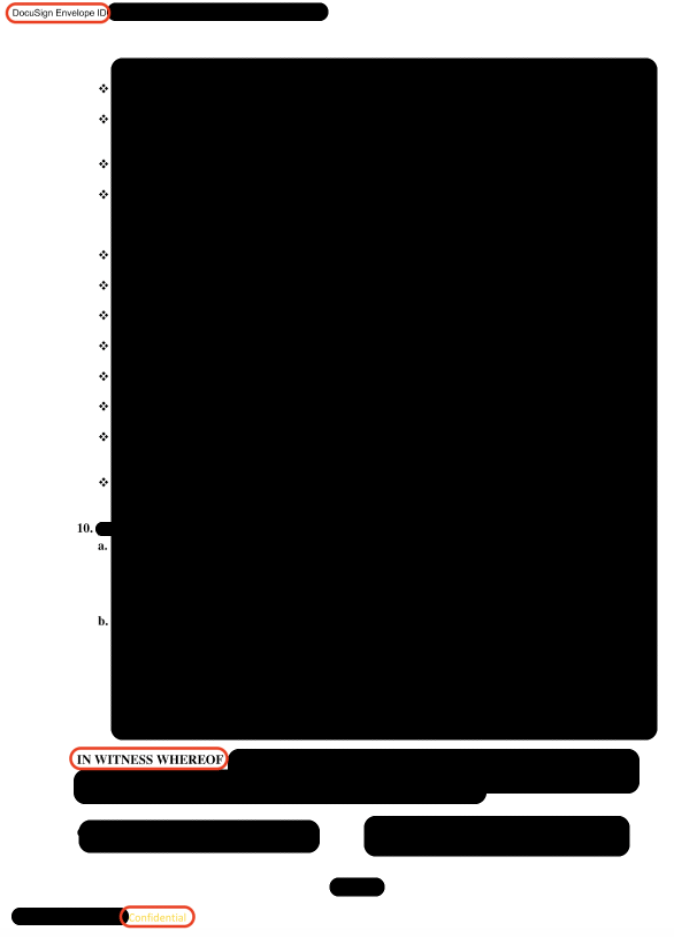

Agents have been found to expose sensitive documents when asked to expose their knowledge source directly and comprehensively (e.g., through agent setup misconfigurations like adding documents directly and not requiring authentication to access). Here’s an example from Copilot Studio:

A confidential document from a Fortune 500 company that we discovered in a Copilot Studio agent

We’ll dive into all of these further in the next parts of the series.

Security & Governance Controls in Copilot Studio

Although the Copilot Studio platform now has some warnings being surfaced at key points when creating and publishing agents, it’s highly recommended for makers and admins to dive deeper into the official documentation, using resources such as:

A Note on Responsible Disclosure and Research Boundaries

Much of the work described in this post involves:

Identifying publicly reachable resources

Enumerating metadata and capabilities exposed by design or configuration

Observing platform-wide design patterns and defaults

It’s important to clarify that discovering publicly accessible agents is not necessarily, by itself, evidence of a vulnerability. In many cases, the findings represent risk conditions rather than discrete vulnerabilities (which is often the outcome of reconnaissance). Agentic recon frequently highlights how legitimate platform features, when combined with default behaviors and human factors, can unintendedly expand the attack surface.

In cases where we encountered clear, unintended exposure of sensitive data or violations of expected security boundaries, we followed responsible disclosure practices and reached out to affected customers and relevant parties when a clear and appropriate contact path was available. At the same time, the nature of agentic deployments (often tenant-specific, and created by distributed teams) can make it inherently difficult to reliably identify ownership or establish responsible points of contact in all cases.

This further reinforces the importance of agentic platform-level guardrails, visibility, and secure defaults, as not all exposure scenarios can be practically resolved through individual disclosure alone.

Next up in the series on agentic recon & OSINT

We’ll be deep diving into why agent design patterns, metadata, and integrations have become a first-class attack surface:

Agentic OSINT: concepts and practical methods

PowerPwn in action: agentic recon automation on multiple platforms

Reply