- Zenity Labs

- Posts

- Moving The Decision Boundary of LLM Safety Classifiers

Moving The Decision Boundary of LLM Safety Classifiers

How a new fine-tuning approach can mitigate the problem of inaccurate safety paths

Background

In the previous post - The Geometry of Safety Failures in Large Language Models - I argued that prompt injection classifier bypass is not about what the input says, but where it goes in activation space.

Specifically, malicious input has a different direction in activation space.

That raises an obvious follow-up question:

If bypass correlates with activation displacement, can we train classifiers to resist it?

Yes, but it comes with trade-offs.

Why Classifiers Fail

Earlier experiments showed something unintuitive but consistent:

Semantics-preserving transformations (leetspeak, homoglyphs, casing, wrappers, DSI) barely affect meaning

But they do move activations significantly

And the amount of movement predicts bypass success far better than where the input ends up

In other words, the classifier isn’t fooled because the input looks benign - it’s fooled because the input took a path it was never trained to recognize.

This suggests a new training objective:

Make malicious inputs harder to move.

Training on Geometry Instead of Tokens

This training method works under the finding that there is a large correlation between where the prompt’s activations reached in activation space - and the bypass rate. Here’s how it works:

Run the baseline classifier on a large dataset, in which all the data-points are malicious.

Split inputs into:

Detected attacks (classifier flags them)

Missed attacks (classifier lets them through)

Treat missed attacks as blind spots

Train the model to pull those blind spots toward the detected cluster in activation space

I call this training methodology ‘Delta-sim’, due to the similarity measure of the activations, and their displacement measure.

Why this is reasonable

If the classifier already detects some attacks, then the representations for “malicious” already exist.

Delta-sim doesn’t teach new features - it widens the malicious route so fewer inputs fall off it.

Real-World Test: LLMail-Inject

I tested delta-sim on the LLMail-Inject dataset, which feature 208,095 real attacks

Baseline Prompt Guard 2 performance was far from perfect - only ±30% of the attacks were detected.

After delta-sim fine-tuning:

99.2% detection on in-distribution attacks

1,826 out of 1,841 bypasses recovered

The following result is real - but it’s not the whole story.

The Catch: Calibration Collapses

When you evaluate across other datasets, something subtle happens.

Yes:

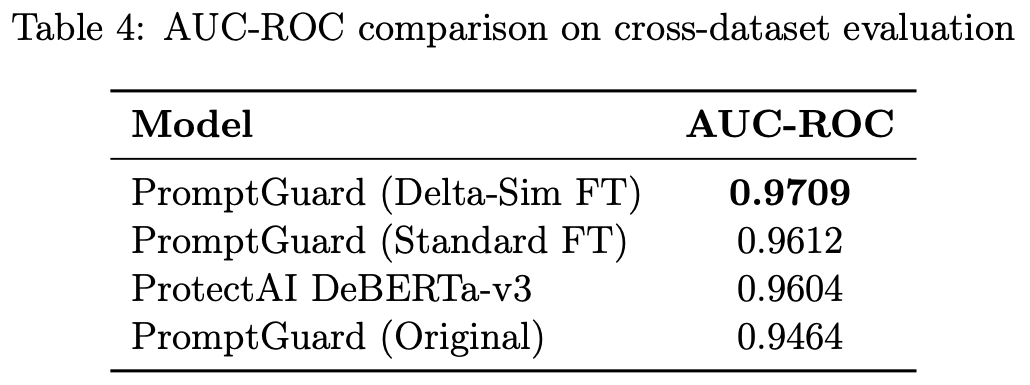

Delta-sim achieves the highest AUC-ROC

Meaning it separates malicious and benign representations better than other models

But:

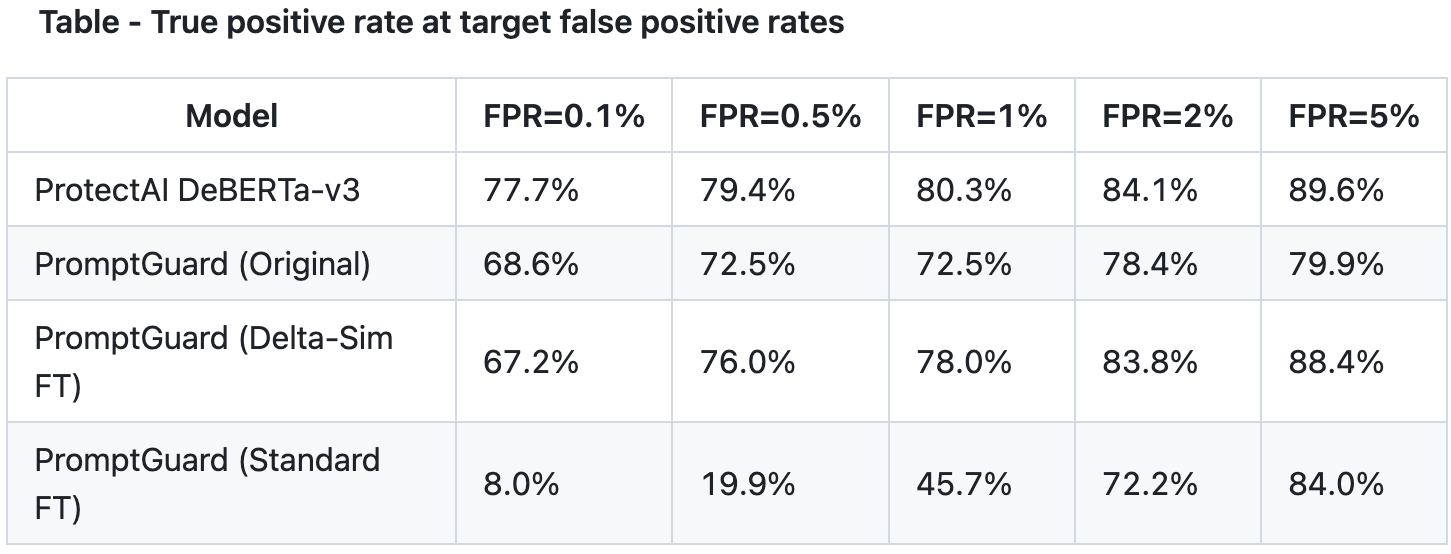

Its probability calibration degrades

Benign inputs start getting extremely high scores

You need absurdly high thresholds to maintain low false positives

At very strict operating points (e.g. 0.1% FPR):

Well-calibrated models like ProtectAI actually perform better

What This Means in Practice

Delta-sim is great when:

You care more about not missing attacks than about occasional false positives

You have human review downstream

You have a low FPR-prefilter before the model

You’re doing detection, logging, triage, or response

Delta-sim is risky when:

You need automated blocking

False positives are costly

Calibration matters more than recall

In short:

Displacement-based training improves geometry, not confidence.

The Deeper Lesson

This work reinforces the same theme as the previous post:

Classifiers already contain useful representations

Failures come from misplaced decision boundaries

Geometry tells you where the model is blind

But it also shows that:

Fixing geometry alone isn’t enough

Calibration is a separate problem

And you can easily trade one failure mode for another

There is no free lunch here.

Conclusion

Prompt injection defenses don’t fail because models are stupid.

They fail because:

Training teaches them where to look

Not how to cover the entire space

Geometric fine-tuning can widen those routes, making the separation of the benign and malicious input better defined, but at the cost of reliability in environments which require lower FPR, like real-time detection and blocking.

Reply